The Castle of Otranto Deconstructs Romance and Realism with the Crash of a Helmet

While early novelists such as Daniel Defoe, Samuel Richardson, and Henry Fielding wielded realism to differentiate their works of fiction from the previous works of fiction published under the romance genre, Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto, which in its second edition published in 1765 declares itself a “Gothic story” (Clery 21), rebels against both: In so doing, Otranto deconstructs the romance/realism binary which prevailed during its time. Walpole tempers the fantastical elements of romance with psychological realism to evade the boundaries of respectability created by the likes of Richardson and imposed by the reading middle-class public–namely, that didactic texts ought to exude believability to adequately instruct the reader. Walpole, himself a benefactor of the traditional aristocracy, employs the emerging genre of the novel to instruct against middle class usurpation and uphold traditional values of the monarchy, all the while wielding the power of horror, fear, and mystery shrouding the dark Gothic period in far-off, Romantic Italy.

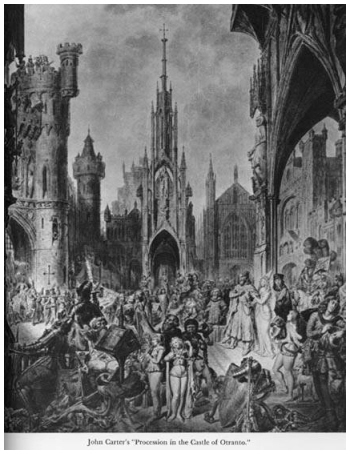

Otranto’s fantastical helmet crashes onto the son of the usurper, Manfred. He and his offspring are held accountable for their ancestor’s usurpation of the Castle, a decidedly undemocratic idea. No one escapes unscathed by this foretold tragedy–not even the fictional genre in which Ortranto presents its ideals. One by one, giant body parts of Alfonso the Good, Otranto’s last rightful ruler, penetrate the castle. His helmet crashes into the court dashing hopes of the royal wedding. His foot and leg slam into the gallery, frightening Manfred’s servants and infuriating him by delaying his incestuous pursuit of his late son’s betrothed, Isabella. Finally, “an hundred gentlemen bearing an enormous sword, and feeming to faint under the weight of it” (51) arrive at the castle gates to claim Isabella. Walpole deconstructs the abstract mystery of the ancestral past by displaying one ancestor’s body broken into individual parts, which the reader and characters must focus on, due to their unrealistic size. Even Manfred cannot ignore the fragmented armor which bring the social construct of ancestry and heredity to life, rendering this abstraction very real to these very fragmented characters, whose psyches Walpole depicts, however simplistic, react to the fantastical circumstances in realistic ways characteristic to their societal stature. The servants Diego and Bianca are first to believe in the mystical reality afoot in the castle, relying on gossip in the servants’ quarters as fact, while the virtuous princess, Matilda, and her father do not believe it until they see it. Matilda reacts much more respectably than does Bianca to the ghostly events in the castle, and likewise is much kinder and more reserved in her analysis of Isabella’s motivation for escaping the castle: she does not rush from mystery into conclusions and, though she accepts the reality of ghosts, responds thoughtfully on how to question them. This trait of the nobility is also present in Alfonso’s rightful heir before he is known, the peasant Theodore.

Fantastical elements not to be believed serve to entertain the reader, and terrify the characters. In this regard, Walpole is more truthful and straightforward than Richardson and Defoe, who presented Pamela and Crusoe as histories or biographies. No one believes this really happened. However, it is also true that Walpole at first claimed Otranto to be an unearthed story from the Gothic period in Italy, a fake fact that was later defanged. Otranto is, paradoxically, a fake, real tale. Unlike the emerging middle class “virtues” we have seen “rewarded” in other 18th Century novels such as Pamela, it is blood of the aristocracy that prevails upon Manfred and his innocent daughter and wife who, though virtuous, perish. Unlike romance and realism, the story of Otranto leaves no happy survivors–unless you count its Gothic-novel offspring.