Tomfoolery as Teacher: A Raucous Romp through Lusty Ladies and Treacherous Taverns Punctuated by Chance Encounters with Good Samaritans with your Host, Parson Adams

Parson Adams would rather be a fool (or play one) than boast street smarts or be wise in the ways of the world, which would have helped him avoid certain comedic blunders throughout the novel Joseph Andrews. He says: “If knowledge of the world must make men villains, may Juba ever live in ignorance (book 3, chapter 5). Adams’s assertion shows that he derives his knowledge from books, rather than experience; he quotes “that fine passage in the play of Cato, the only English tragedy [he] ever read” to argue the point that he would “prefer a private school, where boys may be kept in innocence and ignorance” like he is, when he could just as easily have provided real-world evidence, grounded in facts, to support his solution to a worldly problem.

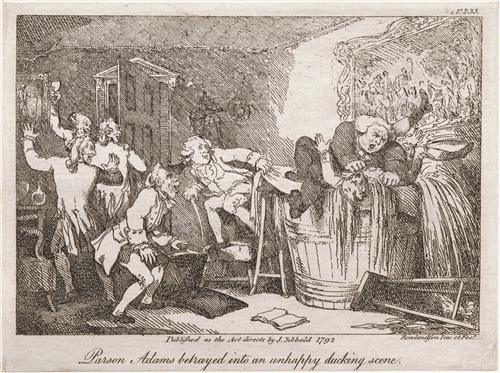

Readers laugh at and with Adams as his entertaining ungroundedness instructs readers of Fielding’s assertions through humor rather than a serious, pious lecturer (such as Richardson’s Pamela, which Fielding here lampoons). Fielding wants us to enjoy our romp through the English countryside as we learn about charity and how to be a good person in general with Andrews and Adams–a bromance type plot which surely gave rise to movies like The Hangover. Adams shows us how not to take ourselves too seriously in the following scenes:

- “Never believe me, if yonder be not our parson Adams walking along without his horse” (book 2, chapter 7): Adams is so absent-minded and unfocused that he left on his journey without his horse!

- “Adams’s foot slipping, he instantly disappeared, which greatly frightened both Joseph and Fanny; indeed, if the light had permitted them to see it, they would scarce have refrained from laughing to see the parson rolling down the hill …” (book 3, chapter 2): Slapstick/physical comedy at its finest.

- “… the captain conveyed his chair from behind him; so that when he endeavored to seat himself, he fell down on the ground …” (book 3, chapter 7)

- The dancing-master no sooner saw the fist than he prudently retired out of its reach, and stood aloof mimicking Adams …” (book 3, chapter 7)

Fielding shows us, through Joseph’s actions, that Adams’s teachings are not lost on his star student, and the parson’s foolishness renders his lessons no less effective. Lady Booby says to Joseph, “Then you are either a fool or pretend to be so” (book 1, chapter 5). Joseph’s either (1) being the fool or (2) acting the fool shows that he takes a cue from Parson Adams, as it results in a successful attempt on his part to avoid sleeping with Lady Booby.

As Fielding puts it in book 1, chapter 1: “The only Source of the true Ridiculous (as it appears to me) is Affectation.” In other words, while Fielding aims to create an enjoyable novel, it is not comedy for comedy’s sake; a didactic and ethical purpose drives this novel. He writes: “It is a trite but true Observation, that Examples work more forcibly on the Mind than Precepts,” “inspir[ing] our imitation” of virtue rather than mere understanding of it.

Similar to how Parson Adams shows us his moral qualities through his actions not just his sermons, Fielding shows his readers, through his own action, that he is not merely critiquing Pamela; he shows, and tells, in his own novel that is just as enjoyable as Pamela itself (and what’s more, less hypocritical in that it does not capitalize on the same sexuality that it denounces).