Field Report: University Archives and Special Collections at Oakland University

On Friday, 24 January 2020, from 9:30 to noon, I visited the University Archives and Special Collections at Oakland University in order to conduct on-site research into materials related to my primary area of scholarly interest, the long 18th century, and emphases, writing by/about women and the history of the self. I examined the archive’s online catalog and engaged in an email correspondence with the archival staff 4 days in advance of my appointment. While at the archive, I perused the 10 items that the Archival Assistant had called up for me, 3 of which I was able to spend quality time with, taking notes and photos depicting their distinguishing characteristics. This post discusses Oakland University’s Special Collections, specifically the Marguerite Hicks Collection of Women’s Literature and its holdings, the items I examined, and their relevance to long 18th-century studies.

The University Archives and Special Collections at Oakland University is comprised of 11 University Archives categories to include Administrative Offices, History, Publications, Meadow Brook Hall, Photographs, etc., (“Archives Holdings and Finding Aids”) and 20 Special Collections that contain “rare books, periodicals and manuscripts documenting the history of Oakland County and Michigan, as well as other topics relevant to research in history, English, political science, art history, theatre, women and gender studies, and other disciplines” (“Special Collections”). While I focused on works pulled from the Hicks Collection, OU’s other collections include the Jane M. Bingham Retrospective Collection of Children’s Literature, papers regarding the death and burial of John Wilkes Booth, Oakland County history, the Oakland Press photographic archive dating back to 1845, an Anglo Irish Collection of an Irish playwright (containing annotations by T.S. Eliot included in the 200 volumes of Anglo Irish literature), the Book Room collection (of 3,000 rare books, pamphlets, and periodicals with first editions of 19th-century American and British literature and including as its oldest book a 1559 Italian numismatic treatise), and several other collections less applicable to my primary, scholarly area of interest (“Special Collections”).

Of the 20 special collections, the Hicks Collection is the most (almost eerily) applicable to my field and emphases; while this collection was not made public during my undergraduate education at Oakland University, I can see myself visiting this collection again (and again) for my research at Wayne State. According to its website, the Hicks Collection “documents the literary production of women, or about women, in the United Kingdom in the 17th, 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries, with the strongest holdings for the 17th and 18th centuries. Some American female writers are also represented. The collection has significant research value and will be of interest to students and faculty in history, women’s studies faculty and English among other fields” (“Marguerite Hicks Collection”). Including works by some of the most-studied early English women to earn a living as authors such as Aphra Behn and Eliza Haywood, this collection is categorized as follows: Cooking and domesticity, Child education, Self help, Children’s literature, Drama, Poetry, Novels, Letters, Diaries, memoirs and autobiographies, Women’s rights, Political satire, Periodicals, and Women’s history (“Marguerite Hicks Collection”). Its emphasis on British 17th- and 18th-century literature—with other centuries and “some American female writers” seemingly present to provide context to them—mirrors my own interests, which aligns my interests with the collector Marguerite Hicks’ and OU’s, which ultimately chooses to curate, enshrine, and market the legacy of Hicks and the women-penned works she collected to scholars, teachers, and students in the local community and beyond.

Due to the vast offering of exciting materials available just under 12 miles from my home, I felt compelled at least to glimpse several (10) texts in a birds-eye view of my most coveted works in the collection, then to drill down to fewer (3) items (one singular work and a pair of companion pieces) to examine in-depth. This would allow for some degree of happenstance during my visit, in case I became more interested in one’s physical appearance over the others. I initially requested to view the following (too many) works: 2 conduct books published by Haywood, The Wife and The Husband (1756); The Female Spectator, volume 3 (1744-46) (the first periodical written for women edited by a woman, Haywood); novels by Haywood (1693-1756) and Aphra Behn (1640-1689); the letters of Mary Wortley Montagu written during her travels in Europe, Asia, and Africa (1785); Lucy Hutchinson’s Memoirs of the Life of Colonel Hutchinson (1808); and Margaret Cavendish’s Life of William Cavendish, duke of Newcastle, to which is added the true relation of my birth, breeding and life. I did not know which of Behn’s works the archive held and thought I would be interested in whatever it held; however, I learned Early English Books Online had identical copies so decided to focus on other texts that did not have digital copies as readily available.

“Of the 913 volumes, 77 were printed in the 1600s, 276 in the 1700s, 426 in the 1800s and 114 in the 1900s”; the Hicks Collection’s website acknowledges that its strength lies in its “17th- and 18th-century works” and not the reprints (“Marguerite Hicks Collection”). Sadly, the Female Spectator was not available, and in the interest of time I eliminated the Behn, Hutchinson, and Cavendish texts, leaving the nonfiction writing of the Montagus and Haywood for my visit. “Many of these works, such as letters, autobiographies, diaries and memoirs, provide wonderful vignettes into life in 17th and 18th century England,” the collection asserts of itself (“Marguerite Hicks Collection”); I concur, and consider OU’s copy of Montagu’s travel writing an exemplar of the “wonderful vignettes” such letters can provide. Wife to the British ambassador to Turkey, Montagu describes in her letters her travels to the Ottoman Empire, thought to be the first secular writing by an Englishwoman about the Middle East and therefore extremely applicable to my field and both emphases. Montagu was apparently an early anti-antivaxer who, after her international travels, advocated for smallpox inoculation in Britain. Her Letters are not only applicable to 18th-century studies and writing by/about women; they also illuminate the history of the self through a woman categorized as gentry class, who traveled internationally and partook in self-fashioning by writing about her travels and, further, by advocating for the care of others, in this case, the health care and network of British subjects.

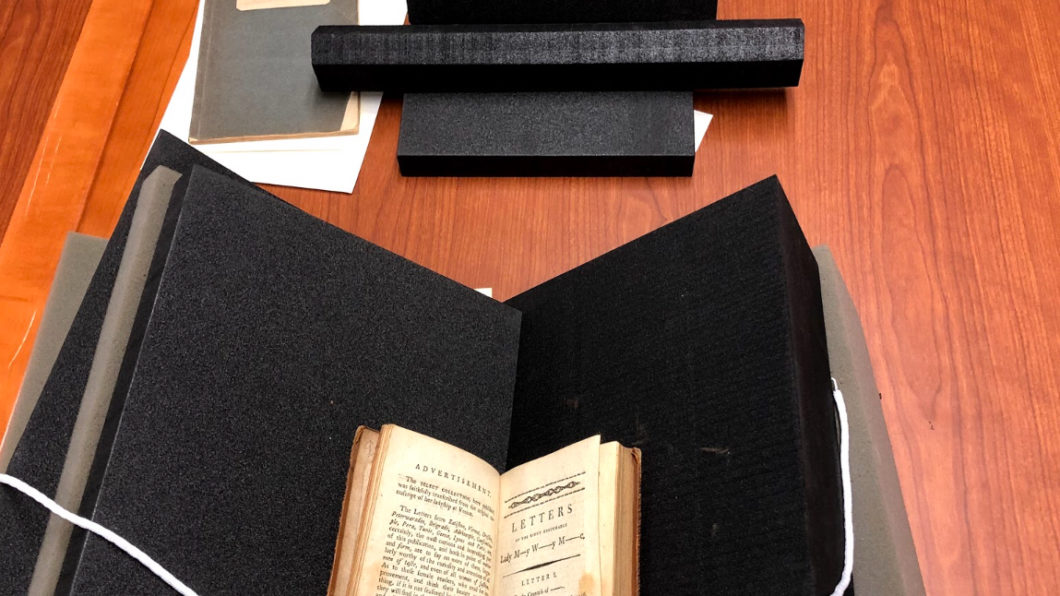

Ready to behold and thumb through these nonfiction works printed during the Montagus’ and Haywood’s lifetimes, with ruler, pencils and tablet in tow, I arrived at the Archives Reading Room (#129) in the Kresge Library basement. I was the only visitor that morning, and had my own table to sprawl out on amidst the archival fodder on the walls such as an early map of OU’s campus plan and President Lyndon B. Johnson’s pens in a shadowbox. Paquette had pulled 4 of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu’s, 2 of Elizabeth Montagu’s (letters and literary criticism) and 4 of Eliza Haywood’s, which were waiting for me on a cart along with props to assist my taking excellent care of the texts such as book holders and snake wrights, and acid-free paper bookmarks. I nervously started opening the creaky texts, some of them requiring more stacked holders than others, all of them requiring my fingers only to touch the edges of the pages and not the center of the paper itself. When I scanned 35 pages of Montagu’s Letters of the Right Honourable Lady M–y W—-y M—-e, for instance, it took longer than I thought due to the creased spine. I had forgotten that old book covers would likely be made of leather or similar material, and learned that higher-priced books would be bound with leather. Experiencing the texts as the authors would have during their lifetime, to include the materials, fonts and water-marks (not all of which were visible with a phone flashlight), left me feeling even more connected to and excited about the time period I have chosen to focus multiple years of study and (hopefully) the rest of my career on, a feeling that lingered for the rest of the day and that I remember now in reviewing my scans and photos from that day.

Works Cited

“Archives Holdings and Finding Aids.” Oakland University Library, https://library.oakland.edu/archives/holdings.html. Accessed: 13 February 2020.

Haywood, Eliza. Entretien des beaux esprits. Conversations, comprising a great variety of remarkable adventures, serious, comic, and moral. Written for the entertainment of the French court. Translated by Mrs. Haywood. 1693-1756.

—. Husband. In answer to The wife. 1693-1756.

—. The Wife. 1693-1756.

“Marguerite Hicks Collection of Women’s Literature.” Oakland University Library Special Collections, https://library.oakland.edu/collections/special/hicks.html. Accessed 13 February 2020.

Montagu, Elizabeth (Queen of the Bluestockings). An essay on the writings and genius of Shakespear, compared with the Greek and French dramatic poets. 1718-1800.

—. The letters of Mrs. Elizabeth Montagu, with some of the letters of her correspondents

Montagu, Lady Mary Wortley. Letters of the Right Honourable Lady M–y W—-y M—-e; written during her travels in Europe, Asia, and Africa, to persons of distinction, men of letters, &c., in different parts of Europe. Which contain among other curious relations, accounts of the pol…. 1689-1762.

—. Works of the Right Honourable Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, including her correspondence, poems, and essays. 1689-1762.

—. Letters and works of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu / edited by her great grandson, Lord Wharncliffe. 1689-1762.

“Special Collections.” Oakland University Library Holdings, https://library.oakland.edu/collections/special.html/. Accessed 13 February 2020.

Books Scanned

Handwritten Letter found in Montagu, Elizabeth’s An essay on the writings and genius of Shakespear, compared with the Greek and French dramatic poets.

Haywood, Eliza. The Husband. In Answer to the Wife.

—. Present for a Servant-Maid.

Montagu, Lady Mary Wortley. Letters of the Right Honourable Lady M–y W—–y M——e.

Plante, Kelly. Photo-Journal of Archival Visit. 24 January 2020.